You’ve heard the stereotypes and, in a frustrated moment, may

even have uttered one or two of them yourself:

- Manufacturing is prepared to make any product you like as long as

it’s black.

- HR cares more about having the latest training program than

about business results.

- Legal should not be involved until it is strictly necessary, otherwise, they will “prevent business.”

- Finance leaders are focused on the numbers, not the business, and they don’t collaborate well.

- The sales team is made up of “target beaters,” focused on volume

but not operations or credit issues.

- Marketers are enamored of big ideas and cool creative, but lack

financial and analytical skills.

- Procurement just wants to buy as cheaply as possible, even if it

causes a problem in the factory.

- IT are tech geeks advocating technology for technology’s sake, or

the “help desk” to be called only when there is a glitch — either

way not very strategic.

- R&D comes up with amazing concepts that nobody can

actually build.

As they move to more senior roles, executives in

finance, marketing, IT, legal, HR and supply chain tend

to develop distinct skill sets, vocabularies, mindsets

and styles. These differences in styles, language and

priorities across functions — the nuggets of truth that

drive the stereotypes — can sow distrust, get in the

way of hearing one another’s ideas or perspectives, and

keep leaders from working together effectively. They

also can prevent leaders from learning useful ideas and

approaches from one another.

Yet the ability of top leaders to learn from one another

and collaborate across functions and businesses has

never been more important, as the most significant

challenges facing organizations — business transformation,

innovation, dynamic competitive and market

threats, and increasing customer expectations —

demand shared objectives, creative thinking and, often,

a coordinated approach. Mobile, for instance, requires

a “triangulation of all forces from customer experience

to technology to marketing to sales to think about it,”

said Erik Pearson, executive vice president and chief

information officer for IHG. Leaders who understand

the priorities, language, styles, strengths and weaknesses

of other functions and business units are at a

distinct advantage as the dependencies across the

organization grow.

Drawing on data about the skills/styles of functional

leaders, our experience assessing them and conversations

with executives who have gained experience in

multiple functional areas, we look at what functional

leaders can learn from other functional areas and

provide advice for integrating diverse perspectives to

improve individual and team performance.

Getting past the stereotypes

Serving in another functional or business leadership

role for a period of time is one way to see other functions

in a new light as well as the limitations of your

own experience. When he moved to general management

from human resources, Juliano Marcilio was able

to combine his expertise in talent management with a

new view of the challenges of the business — specifically,

the need for the sales organization to evolve in

response to the company’s new, more complex multiproduct

strategy. Under his leadership, the unit

changed the profile for new sales team hires, oversaw

the creation of new training programs and implemented

significant changes in compensation and

incentives, improving the performance of the business

unit. “By applying a much more insightful HR strategy,

we managed to change the game,” he recalls.

Returning to an HR leadership role a few years later —

as head of human resources for HSBC Bank Brasil —

Marcilio drew on his general management experience

to realign HR performance measures to the performance

of the business. Creating measures for

assessing the quality of management, they determined

that, indeed, good managers had better business

results, and learnings from that work fed improvements

to the HR processes of the whole bank.

Like Marcilio, Alfredo Ferrari, now CEO of Siqueira

Castro Advogados, found himself having to think differently

when he moved from legal to general management.

“I thought I could apply my legal training and

modus operandi directly to GM. Being a GM is a

different ballgame from my previous legal experience.

A corporate lawyer sometimes does not have a full

operational view of the business. A lawyer thinks,

analyzes and ponders variables. A GM needs to say

‘yes’ or ‘no,’ has to take decisions and make them

happen, has to forecast what is the best for the business,”

he said. But Ferrari also found that his knowledge

of the law and ability to consider tradeoffs allowed

him to more confidently weigh risks and decide which

risks to take. “A ‘normal’ GM would probably be more

cautious, unsure about the true consequences for the

company and maybe himself. On the other hand, when

I said that something could not be done, my business

team understood it.”

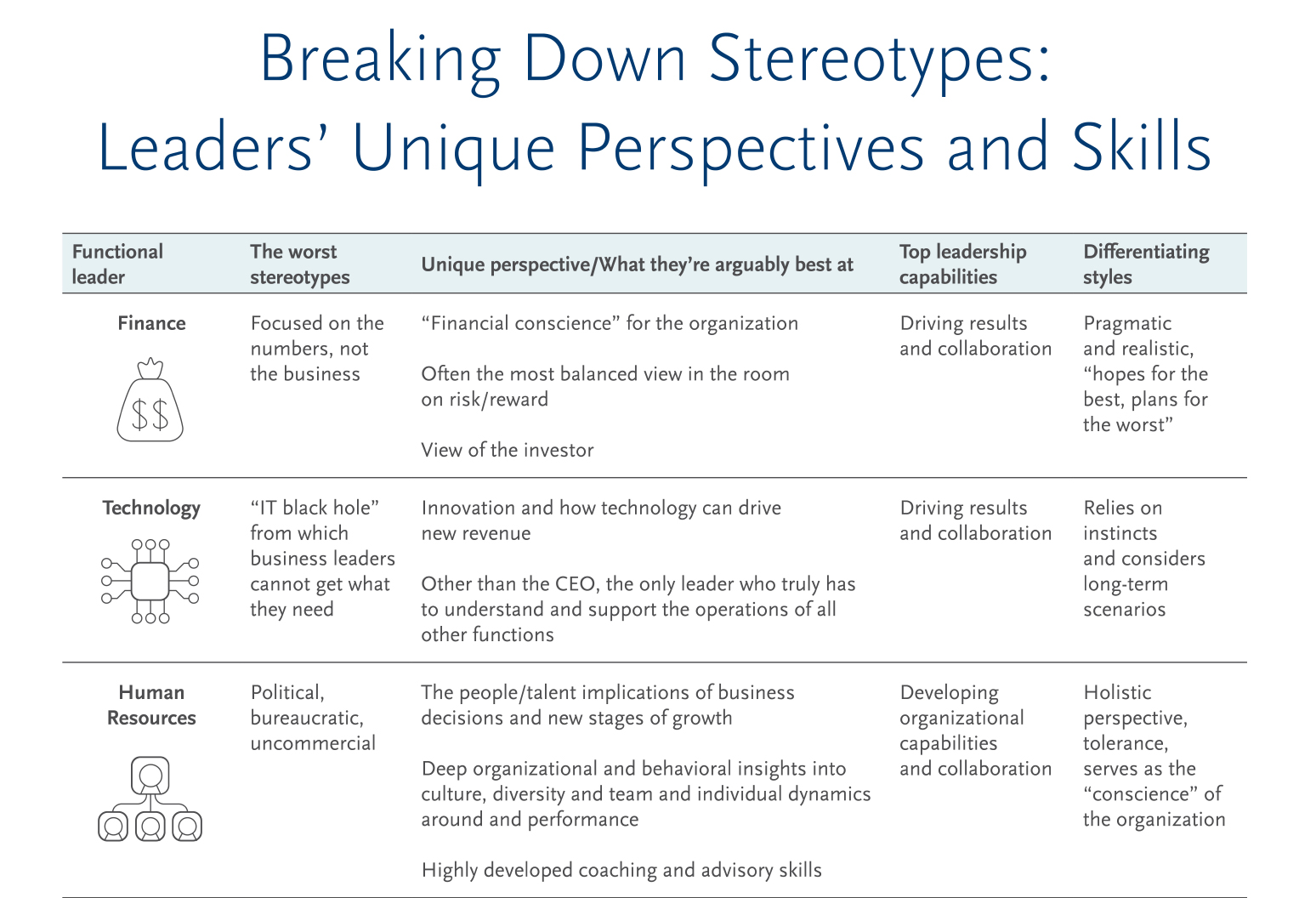

View full image

These kind of experiences that provide deep insight in

new areas of the business or fresh ways of thinking

from another functional or business area can be transformative,

said Pearson, who went from a global team

role running the internet business to a regional CMO

role and ultimately into the CIO role. “Your ability to

have a broader impact and influence organizationally

on the company improves when you move from function

to function or from the U.S. to China. It enhances

your understanding of customers in different markets

and different demographics and how that impacts your

business decisions as well as your technology decisions,”

he said. “These experiences also can increase

the ‘speed of trust’ — accelerate trust in the organization

so that people can make decisions faster and actually

go to market faster.”

But even without changing roles, leaders can find ways

to gain important insights that lead to new ideas and

improved ways of working, breaking through stereotypes

and political and bureaucratic divisions that get

in the way of doing what’s right for the business.

“Solutions can emerge when you bring people together

and get at what’s driving those perceptions,” said

Richard Ware, who began in Mars R&D function, later

spent time in supply chain and procurement, and now

heads up supply chain, R&D and procurement for the

company. For example, insight from marketing about

the drivers of consumer decision-making helped R&D

refine its approach to innovation.

Appreciating the unique perspectives and capabilities that other functional and business leaders bring to the table — and tapping their expertise

— is a good way to start breaking down barriers.

“One of the best insights that we had from the

marketing team was around the ‘laws of growth,’

and the realization that the world isn’t out there

waiting for a better Mars bar,” said Ware. “There are

reasons why people don’t buy our products that may

become the barriers: ‘I can’t find it in the store.’ ‘I

can’t afford it.’ ‘I don’t think of it, or it’s not relevant

to me.’ Once you have the clearest possible articulation

from marketing about the opportunities, product

development can get much more to work.”

The ability to learn from other functional leaders requires

both mastery of one’s own area — which earns leaders

the right to contribute at a broader level — and the

self-awareness to seek out the best ideas and approaches

from others, said Robert F. Probst, executive vice president

and CFO of Ventas. “Not everyone brings the same

strengths to the table. By definition, functional leaders

excel in different areas. Teams come to a better result

when the best ideas are actively sought out from different

people. Just as it is critical to know the complementary

sweet spot of peers so those strengths can be leveraged,

it is important to be self-aware, to keep an open mind and

to listen,” he said. “For example, finance professionals,

who might not have a reputation for not being as focused

on softer skills, can learn from other partners like HR.”

View full image

Breaking down barriers: What leaders can do

Sharing ideas and best practices and improving collaboration

across functions and businesses don’t just

happen. Organizations that do these things best have a

shared vision for the business, maintain a culture that

encourages learning and establish decision frameworks

that ensure collaboration doesn’t result in indecision.

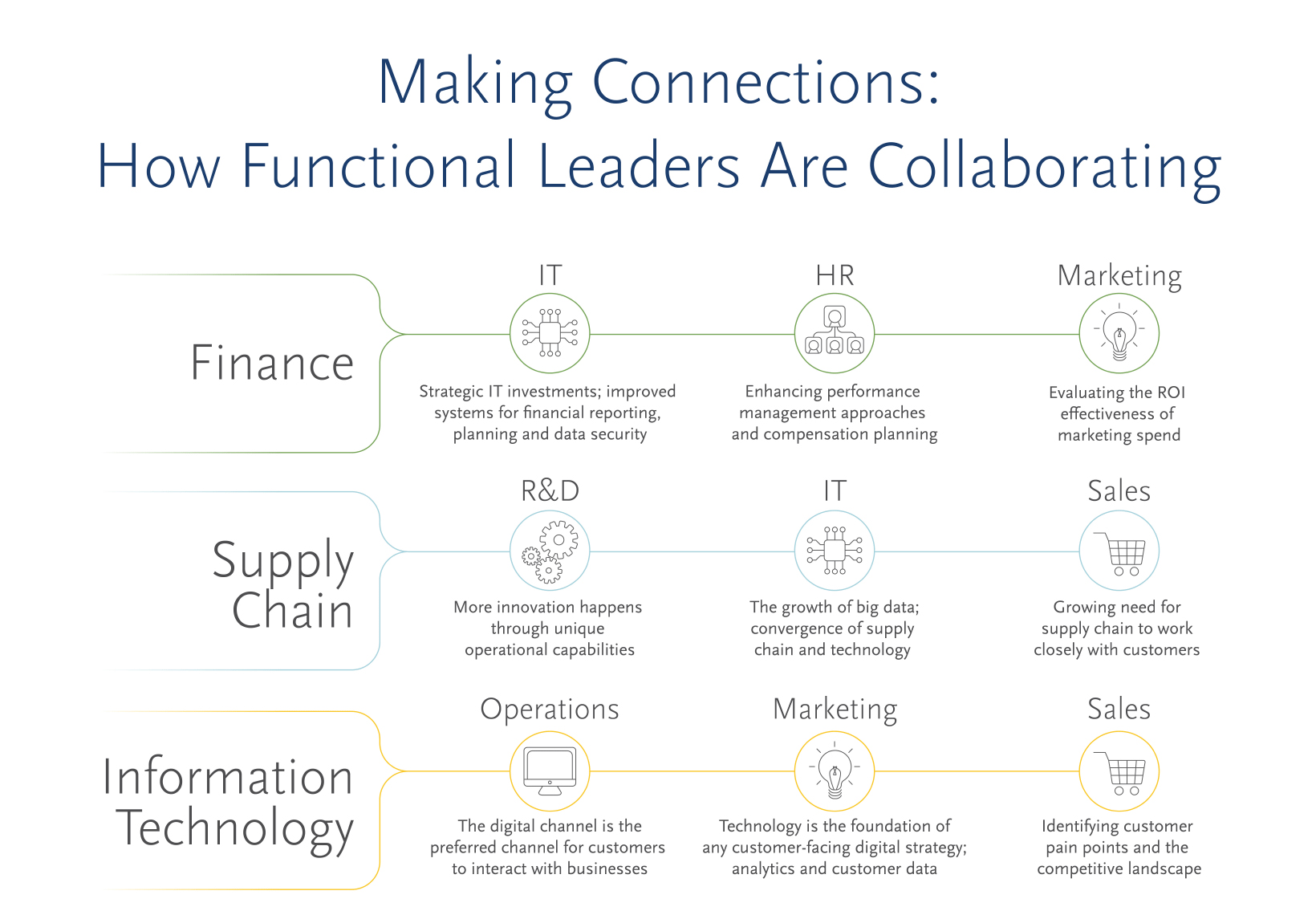

Understand and tap the diverse strengths

and ideas of different disciplines

Appreciating the unique perspectives and capabilities

that other functional and business leaders bring to the

table — and tapping their expertise — is a good way to

start breaking down barriers. For example, our assessments

of the core leadership capabilities of thousands of

functional leaders have shown that IT leaders tend to

excel at driving results and collaboration, while chief

human resources leaders are strongest at developing

organizational capabilities. Beyond the capabilities, functional

leaders also develop a unique view of the business

based on where they sit. Good supply chain leaders have

a great view of the cost of doing business and the implications

of decisions on the product and delivery, while

strong marketing leaders can have the best insight into

how decisions may affect the customer or the brand.

Insights from other functions include the following:

- From finance, a focus on ROI and P&L and balance

sheet management, and the insights that drive

investor perceptions

- From general management, the discipline of evaluating

issues first from a whole-business lens before

the functional perspective, and a focus on finding

ways to create value

- From IT, the ability to “look around corners” and spot

the threats that could transform or disintermediate the

business; agile approaches to rolling out new ideas

- From human resources, the drivers of values, behaviors

and performance from a people perspective

- From legal, the balancing of risks and rewards

- From sales, the specific challenges and needs

of customers

Absolute mastery of their own functions enables leaders to translate between the function and the broader business,

which is critical for promoting understanding, said

Ware. “A key role as functional leaders is translator —

translating what is important to the function in a

vocabulary that the business can use and translating

what’s important to the business or another function into

the vocabulary and actions the function can use,” he said.

Clearly articulate the contribution of each

discipline in the larger business vision

“The most successful companies inspire people to see

how they fit within the larger mission, creating the belief

at all levels of the organization that what you do

matters,” said Pearson. “Whether you’re a developer, an

analyst, a data scientist, whatever, what you do matters

because it has a direct impact on our guests having the

best stay or our employees having the best environment

to work in or our owners loving our brand.”

For functional leaders, aligning with the business

agenda means understanding how the function

impacts the business and whether it’s contributing to

business performance or not.

“If you’re sitting in a function, you have to make sure

that you understand the overall business agenda and are

aligned with it so what you’re actually delivering is really

driving the business objectives, because that’s the only

thing that counts at the end of the day,” said Doug

Baillie, who recently retired as chief human resources

officer of Unilever. In a rolling two-year cycle, Unilever

senior teams helped by HR conduct an audit of talent,

organization, culture, skills and capabilities in their parts

of the organization — be it a geography, category or

function. “We ask: What’s our talent strength? What do

we need to do in the organization? What skills and capabilities

are missing, and what are the things we need to

strengthen from a culture point of view? We map that

against where the business is today and against their

three-year strategic plan,” said Baillie, who came in to

HR from a line leadership role. “From there, we focus on

delivering no more than 10 people actions, which are

owned by the business, in order to make sure what HR

is working on is truly driving that business agenda. It’s

the most powerful tool that I’ve seen for ensuring that

our agenda is really aligned to what the business needs.”

The CEO sets the tone for collaboration by articulating

the vision and demanding business metrics and performance

objectives for functions and business units that

are linked by the shared vision. “The CEO must tailor

communication to each function, demonstrating the

impact of each area on the work of the others and on

the ultimate client. At Siqueira Castro, we have an

all-hands 45-minute meeting every Monday morning,

revisiting what our corporate goals are, what each

major area is doing to achieve them and foster collaboration

and communication. I ask each senior executive

what they will do that week to move us closer to the

goal. This clarifies everybody’s roles, to themselves and

to the others,” said Ferrari.

The CEO also is critical to creating a culture that fosters

an environment of constructive debate, Probst said.

“The CEO needs to be a role model that seeks input

across different areas. He or she needs to seek input

and flip to either side of the table to encourage debate.

The best organizations encourage their leaders to call

each other out if they do not agree on an issue. Equally,

then they need to coalesce and respond with one voice

and with speed once a decision is made. The key to

creating this kind of culture is trust, high performance

in each function and a willingness to collaborate.”

Establish clear decision frameworks

When collaboration becomes consensus — and

everyone has veto power — decisions can be delayed

or perpetually re-debated. A key to effective collaboration

is defining a clear decision framework that articulates

who is responsible for making certain decisions

and who has the right to contribute to or veto a

decision.

“Tensions arise where there is a lack of clarity,” said

Baillie. “In a matrix organization, two things can help.

Firstly, minimize the number of points in the matrix

when decisions get made and be clear who makes

them. Secondly, accept that there will be conflicts and

that conflict is generally healthy. The question is how

conflict is handled when it does arise. Many matrix

organizations suffer because conflicts brew at a very

low level in the organization, rather than being escalated

and resolved. Successful companies quickly

surface and resolve conflicts.”

Ware agreed: “Succeeding today is about speed, so

large companies have to figure out how to reduce the

number of ‘maybes,’” he said. “One of my colleagues

has a great line: ‘I’d like a yes, I can live with a no, what

will kill me is the slow maybe.’ So we’re focused on

avoiding the slow maybe.”